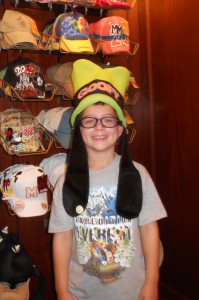

The eyelid is involved in many diseases that we see and treat on a regular basis. Its function to protect the eye is an important one, whether it be to act as a barrier to prevent direct trauma, to limit bright light irritation or to distribute the tear over the corneal surface. Some species have an extra lid where others have no lids at all! I’ll take a couple of posts to address the lids and we will concentrate on congenital issues here. So take off your lid and stay awhile as we talk about the eyelid and some of its special features and disease presentations. If you are lucky enough like my son Reggie who was recently in Disney, your lid may even have ears on it!

Eyelid anatomy

There really is not much to the eyelid. Skin is on the outer surface with a relatively normal makeup of hairs, feathers, or scales and glands. Not all animals have eyelashes, though, and most domestic animals don’t have lashes on the lower lid. A hairless region at the lid margin maintains a smooth surface for contact with the clear cornea and help with tear distribution. In addition, tiny meibomian glands produce an oily substance that helps keep the tears from evaporating. This material exits onto the corneal surface from small pores at the lid margin. The muscle that closes the lids is called the orbicularis oculi and surrounds the eyelid margin as one might expect. Contraction closes the lid and relaxation opens the lid with a little help by another muscle called the levator palpebrae superioris that lifts the upper lid. The inner aspect of the lid is lined by conjunctiva which, in this location by the lid, have special goblet cells that secrete another component of the tear film that allow the tear to “stick” to the cornea called mucin. Admixed throughout these structures is connective tissue.

Mammalian lid cross section.

Many species have a third eyelid which also helps dispense and distribute tear. In mammals, it is usually located in the inner, lower aspect of the eye and comes up passively whereas in birds it is located in the upper inner quadrant and can be actively moved. In our dogs and cats, the gland of the third eyelid is an accessory gland that produces 35% of the watery tear and is located at the base of a “T” shaped cartilage that gives the membrane some rigidity. I could go off on bird third eyelids but will save that for another posting as that is one very cool structure!

It just ain’t built right!

Congenital diseases in our patients that are associated with the lids are relatively uncommon. The two most prevalent are lid agenesis, most commonly seen in the cat, and dermoids.

Lid agenesis is a prominent lack of lid tissue development that affects the lid margin. Instead of having that nice hairless zone with the meibomian glands and their related pores, there is a stark transition from conjunctiva to the haired skin. This creates a local region of irritation and lack of protection for the adjacent cornea. Cats may present for discharge and squinting from the skin hair that is now directly rubbing on their cornea while some seem relatively content. With lid closure, a noticeable gap is present which predisposes the adjacent cornea to scarring, vessels or ulceration. This can involve one or both eyelids.

Lid agenesis of 2/3 of the upper lid in a cat.

Treatment of these lesions are aimed towards decreasing or stopping the local irritation from offending hairs and/or improving the coverage of the exposed cornea. Reconstruction of the lid using grafting techniques to slide tissue into the gap are well described with variable success. Although these are geared to “filling the gap” from the lost tissue, hair irritation may still be present and need to be managed depending on which direction the hairs on the grafted tissue are directed. Another method of treatment, which I use more commonly, is to address the offending hairs by using cryosurgery to make the region bald and leaving the gap alone. Cats do amazingly well with this approach as the exposed area rarely ulcerates and extensive changes associated with pigmentation, vessels and scarring into the more normal cornea is uncommon. The procedure is tolerated well, does not require suturing and is usually only needed once although repeat surgery is always a concern with either approach.

A dermoid is simply a piece of skin in an abnormal location. In the eye, this usually will result in a distortion of the lid in the region or a patch of haired tissue on the conjunctiva or cornea itself. The hairs are typically irritating so a degree of mucus discharge is not uncommon. Resection of the skin from the abnormal location is curative and regrowth does not occur unless a hair follicle is left behind. This gives a new meaning to the term “hairy eyeball”!

Dermoid on the cornea of young Shih Tzu.

Eversion or scrolling of the cartilage in the third eyelid is another congenital entity that we may see. The third eyelid, or nictitating membrane if you want to impress your friends, should conform to the cornea as it floats over the surface to distribute the tear. The cartilage is what maintains this shape. Some dogs have a predilection for this cartilage to bend usually away from the corneal surface which gives it a scrolled appearance and affects its optimal function. Surgeries have been described to correct this condition by resecting, reversing or stretching the bended section to try and create a more normal lid/corneal relationship. We are currently publishing a technique using heat to remodel the cartilage that shows a lot of promise and is less invasive than other techniques. Here are before and after images of a dog treated in this fashion.

Everted cartilage of the third eyelid

Postoperative appearance of scrolled cartillage after remodelling

This is just a sampling of some of the changes we can see on the lid. Remember, congenital does not necessarily mean genetic! Events can happen during the pregnancy that change how tissues develop rather than having a genetic predetermination that a certain disease or anatomical change will develop. We will talk about some genetic and acquired conditions of the lid next time!